FOREST FLOOR

Ecology news

Use local forests as your textbook.

Let go completely of the idea that nature is to be tamed and subdued.

We had to let go of common notions of planting trees. Planting trees is a relatively new art (and a new science) anyway, we humans having spent most of our recent years chopping them down. We had to observe nature. We observed ourselves working away, so busy that we were continually deluding ourselves that we were taking steps forward. As we looked more closely still, we found that we were actually going backwards sometimes. Not only was the customer wrong, we were wrong, because we were following the customer. Not only that, the customer wasn't listening to the crucial bits, where we tried to wire our own angle into the landscape plan. We ended up just giving all our ideas away, rabitting on in conversations to people who had preconceived ideas, who didn't listen anyway, they just wanted us to nod our heads and make them feel good. It was the emporor's new clothes syndrome.

There was nothing for it but to tell the truth, wild as it may seem, its out there for anyone to check up on us if they care to observe too. We tell them to do nothing.

We want people to stop for a moment, to stop near the edge of a forest, to stop so still that they see over the next few moments a new experience filtering in, the experience of being there. Like when you hear for the first time a new bird noise in your planted forest on a fresh spring morning, carrying sweet through the air, mingling with the smell of lush oxygen rich forest, like when you see for the first time five whiteeyes all eating manuka flowers on the same bush that you planted outside your door about 3 years ago, wow that was worth doing, that job.

Augmenting the natural process

In nature, plants colonise a hard site all by themselves.

Usually there will be a gradual succession of plants that grows into a forest. Over time the carbon content builds up, until the trees are not even growing on soil any more but on a raft of carboniferous decaying plant material that is held together by a huge web of fungi and roots. Huge forests are able to become established on hard ground.

Virtually everywhere that is now land was at one time covered in trees. Trees (or more specifically, plants, including algae) have been responsible for fixing huge amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere creating the climate that we have on earth now. All by themselves, without humans planting them.

The best thing for us to do as humans is to encourage the natural process of regeneration. We plant a few tough pioneer trees like manuka or kanuka or flax or cabbage trees, to achieve a canopy closure. Then we stand back and let the complex forest system recreate itself. We might have to weed occasionally, but its important not to get too carried away. After a couple of years, once the weeds are starting to get shaded out, we might plant a few more species as seed sources, if there are no natural stands of those trees nearby. In this way we augment the natural process.

The natural process will be towards a predominance of woody colonisers that eventually close the canopy right up. Manuka and kanuka will not do that, they allow some light to filter through their fine leaves, allowing other trees to get going underneath. Eventually broad-leaved species that are more competitive still, will get going and overtop the manuka, excluding still more light, so that all but the most shade tolerant plants are excluded. Eventually those trees get big enough to support hundreds of other species in their canopy. Under the ground, huge colonies of fungi sread across the ground, transporting nutrients to trees. The humus layer, full of microorganisms, build up. Shadeloving ferns and palms get going low down, and under these there are sub-shrubs and algaes and mosses. Every bit of light gets used up, every nutrient gets used efficiently. No wonder that such systems can support such a huge population of bird life. The potential for increase in bird population across this country is massive.

The birds will spread seeds if you plant trees for them to land on and nest in. They will move in and you'll get seeds of all sorts of local fruits germinating underneath a tree. Longer lived tree species take over, unless some disturbance takes place.

Canopy closure

is the ultimate aim of revegetation, then so much light get used up by the trees that few weeds can grow underneath. With its deep root system, an evergreen forest like we have in New Zealand stays dark green and grows year round. It is a much more efficient system for utilising sunlight than a shallow rooted crop. With cunning management systems we can steer the natural processes in directions that support more life. We can speed up the process by well timed action; planting a tree at the right time of year, setting traps, collecting seed, chopping off a branch or two, generally reducing the competition towards the plants you want to favour.

Above all, plant what will definitely grow. That's why we usually suggest that local native pioneers are a good place to start if you wish to cover bare land with trees. Everything does better with a bit of shelter, and what you want for shelter is something that doesn't get disease, doesn't blow over, handles the local conditions in other words. Later on when you hear about our mulching systems for growing fruit trees you'll be glad of every bit of carbon you've got, and if you plant manuka you'll certainly be glad of the firewood you'll get. Meanwhile the trees will absorb carbon and build up carbon and fungi in the soil so that a huge range of plants will start growing all by themselves, leaving us to pull out the weeds.

If we don't do it, grow trees that is, then we will witness the decline of numerous species. If we do, then we can have kiwi in our back yard

Encourage

natural regeneration.

The fastest, most efficient and cheapest way of planting

great numbers of trees is to encourage natural regeneration.

Land left alone undergoes natural regeneration into woody

perennials and, subsequently, tree species.

Every species of tree does better with shelter. The first thing to get

started are the toughest plants. Shrubby

pioneers usually do better in open sites, and out-compete anything else in that

situation until it changes, until it creates a microclimate for forest floor

seedling germination of other species. Pioneers will not normally grow in their

own shade, so they eventually become superseded by species that are shade

tolerant.

For example Gorse is a valuable plant in its role in

providing a canopy-closure for pasture. It regenerates in manuka and kanuka,

which in turn shades out the gorse. After many years the surface soil following

such a succession is a rich composted humus.

The aim is to achieve canopy-closure as quickly as possible.

In order to

achieve this one simply encourages natural regeneration.

This is the most efficient means of planting any block of land because

the pioneers are the easiest to grow and therefore the cheapest.

One would struggle to stop them growing, should one be foolhardy enough

one would work all one's life at it, pushing

a barrow up an eternal hill. To

hold back succession is futile. The secret is to steer it slightly with as little effort as possible.

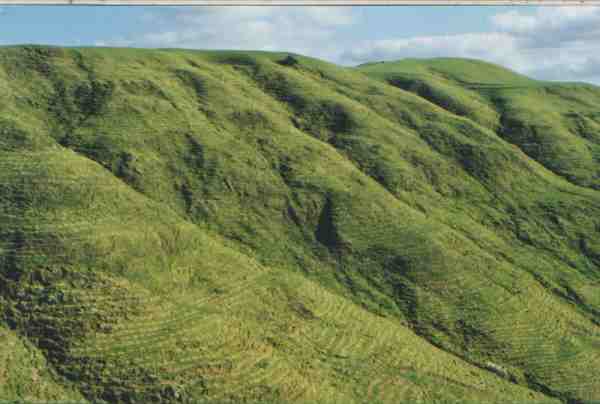

In the example below, manuka seed would get lost in the kikuyu. If all the kikuyu is sprayed off there could be massive erosion. It was easier to plant manukas into sprayed spots. It wasn't exactly easy at the time, but now it is a forest it is very encouraging. And we learnt more, how to do it more easily next time.

plant the toughest local natives.

For the most effective regeneration, you are aiming to establish a nurse crop that will rapidly cover the area and provide protection for the next stage. So at the start you will need a lot of plants that are cheap and easy to grow. You may need to experiment a bit. To find out which method suits your site best, have a look around your area to see what grows naturally, which young seedlings come up easily. Look where they are growing and learn from them. At the start you will be particularly interested in ones which appear to be able to survive frosts, droughts, floods, possums and other such threats. So use your nearest local forest as your "textbook", provided it's similarly situated.

Encourage the growth of large numbers of early colonisers

to establish a nurse crop. Good plants are manuka, kanuka, coprosma, cabbage

trees and flax. It may be necessary to plant or direct seed these plants to get

them going, and if you do, they will take over, providing an ideal environment

for the next stage of forest to develop. Birds

will bring in seed, and the fungi populations will build up to be able to absorb

every bit of input and turn it into something more efficient, more productive.

If you think you can speed it up by planting trees, then choose tough

trees for maximum success rate.

Plant lots of flax, particularly around edges, bad erosion spots, and for shelter for planting other things. This is cheap and effective, particularly if you have a nearby supply of large plants which can be cut up. Cut back the flax before planting and plant firmly as they tend to be top heavy. The flax will also bring in birds which will disperse native seeds from any adjoining forest and do the job for you. Flax is not always a natural early coloniser, however the maturing bush will eventually crowd it out.

Other good early colonisers are cabbage tree and coprosma species, but get rid of all animal pests first. Study your area. If you have forest with karaka you may notice that it comes up readily in grass around a tree. So try direct seeding in grass, making sure the seed is lying firmly on its side on the ground.

Encourage bracken. This is a long-term way to get back to native bush, but nature uses it to good effect as the bracken builds up a good layer of humus for future plants to enjoy. Your site needs to be adjacent to existing bush so birds can bring in the seed.

If it is not easy to encourage natural regeneration because

of thick pasture cover and the process needs to be speeded up, one of the most

efficient methods is to plant the toughest local natives.

In much of New Zealand, and parts of Australia,

Manuka, Leptospermum scoparium to

the botanists, tea-tree to locals, scrub to farmers, is the single, best

toughest species, followed closely by Kanuka. Kanuka is

a superior tree if the situation is pretty dry, but it can't handle really moist

sites lie manuka, nor really nutrient deficient or toxic sites.

Kanuka is longer living than Manuka.

The penalty paid is that it is slower to establish initially which can be

outweighed by its drought hardiness. Kanuka

does not establish itself from seed as readily as Manuka and is thus more difficult to

establish. Manuka

has the ability to prolifically

produce seed, which is then stored on the bushes enabling it to be grown and

planted cheaply in the nursery.

All we found we needed to do on most hard sites was to plant mixed manuka and kanuka at a close spacing over the entire site, then watch it grow. The job was done once those trees had a few roots in, after a few weeks in the ground.

Cabbages trees and flaxes were good too. They grew just about anywhere.

Totara would rank

next. Ngaios would be the next best if it were not for the fact that it is

difficult to obtain seed and they are poisonous to stock which causes management

problems because stock do eat them.

Pittosporums:

Lemonwoods on inland sites, Karos

on coastal sites and tenuifolium on

both have to rate amongst the top species as well but there is more difficulty

in propagation and, once again, they are more costly at the nursery level.

Coprosma Robusta

is an extremely good performer on tough sites but is susceptible to catch the

virus to which the yellows such as Cordylines

and Puriris are also particularly

susceptible. Coprosmas are so fast growing and more succulent and edible by

stock, compared to Manuka which is one

of the most resistant plants to browsing from animals.

In wetlands Carex secta has proved to be the best for us, being a very

long lived and vigorous grass, producing a huge amount of seed, enough to feed

flocks of birds.

The cheapest way is to plant Manuka or, even cheaper, to encourage its natural regeneration.

Sometimes it is necessary to plant small manuka plants, rather than rely on it

to come up naturally, because one wants to speed up the job, to ensure that the

result includes more manuka and less gorse, for example.

If one is not in a hurry then manuka will get going on bare dirt all by

itself, if seed is available.

Manuka will come up thickly on bare dirt, and has adapted

over thousands of years to be able to do so.

If bare dirt is not immediately available from landslides or building

work, then one can be created by cultivation on relatively flat, rock free

ground. Seed can be sown directly onto the surface of freshly turned earth in

early Spring.

The main problem with direct sowing is weed competition. On steep sites that are covered in kikuyu in a subtropical climate, the kikuyu is very competitive. It may be dangerous to attempt to spray it all off and sow see, because of the amount of time the ground lies bare, subject to erosion. One good hit with a whole heap of small vigorous seedlings can speed things up by 6 months to a year, and increase the predominace of manuka in the final crop.

Recently I visited a site on the side of a new motorway,

with Dave, an international forestry consultant. He is amused to know I have made a business out of a weed

like manuka, so he showed me a modern way of doing it.

ďSpecial reveg fabric, engineering textile they call it,

imported at great expense from America, according to the engineers.

Check out what these turkeys are doing.Ē

A vast hillside was covered in a blanket of this new

multitier fabric. Underneath it the

ground had been cultivated with heavy machinery.

Bare chunks of clay lay like blocks.

Topsoil seemed destroyed, although grasses were germinating, indicating

at what stage the succession was. Here

and there manuka could be found germinating from seed that had been scattered.

Well, itíll work.. You canít stop it working.

As Dave says, ďall you have to do is leave it.Ē Thatís the answer. He pointed to nearby gorse and manuka bushes. Thatís what will happen if you leave it. Thatís what they want isnít it?

ďToo simple for them, mate.Ē

The thing is, how gullible are the people who try such things, thinking technology is going to provide the answers, instead of nature and good old skilled labour. I suppose you have to try it to experiment. But the result will probably be that it is a complete waste of time. You will achieve the same result if you did nothing.

We are reminded of the Taoist adage "when nothing is done, nothing remains undone"